This chapter examines the two-hurdle approach in more detail, wherein this information is based on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 78 to 84.

First and second hurdle

Patent eligibility, the first hurdle, is to be assessed under Article 52 EPC without considering the prior art, i.e. without regard to whether computers existed at the priority date of the invention. The use of a computer in the claimed subject-matter therefore makes it eligible under Article 52 EPC.

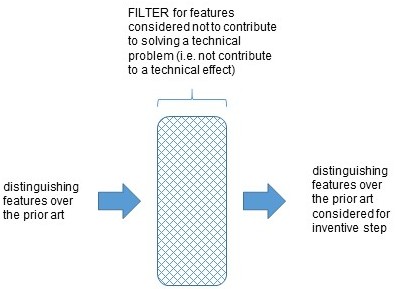

For the second hurdle, the prior art is to be considered. Inventive step is based on the difference between the prior art and the claimed subject-matter, please see figure below.

The requirement that the features supporting inventive step contribute to a technical solution for a technical problem means that the invention, understood as a teaching based on existing prior art, has to be a “technical invention”. The use of a general-purpose computer always constitutes prior art in this context, please see figure above.

Hence, the invention to be assessed under this provision needs to be “technical” beyond the use of a general-purpose computer. For this assessment, the definition of a technical invention in Article 52 EPC, in particular the list of “non-inventions” in Article 52(2) EPC, can be useful for determining whether specific features contribute to inventive step (see G 3/08, Reasons, point 10.13.1).

Technical features per se may not contribute to inventive step

In general terms, features that can be considered technical per se may still not contribute to inventive step if they do not contribute to the solution of a technical problem, please see also the example in chapter (3) “COMVIK approach”. In line with this principle, a technical step within a computer-implemented process may or may not contribute to the problem solved by the invention.

Example: In case T 1670/07, the claim was directed to a “method of facilitating shopping with a mobile wireless communications device to obtain a plurality of purchased goods (…) from a group of vendors located at a shopping location”. The board found that the intrinsic technical nature of a computer-based implementation was not enough to make the whole process technical since the “selection of vendors” presented to the user in the course of the claimed method was not a technical effect, and the transmission of the selection no more than the dissemination of information (Reasons, point 9).

While Article 52 EPC is taken as the framework for determining whether there is a technical invention, the COMVIK approach applies the same criteria in the examinations whether the claimed subject-matter fulfils the provisions of Article 52 EPC and whether any distinguishing features may be considered for the analysis under Article 56 EPC. If, for the inventive step analysis, only those differences from the prior art are to be considered which contribute to solving a technical problem, then this requirement serves as a filter through which the features distinguishing an invention from the prior art must first pass, please see figure below.

Specific effect has to be achieved over the whole scope of the claim

It is a general principle that the question whether a feature contributes to the technical character of the claimed subject-matter is to be assessed in view of the whole scope of the claim.

Using the problem-solution approach, the analysis under Article 56 EPC may reveal that a specific problem is not solved (i.e. a specific effect is not achieved) over the whole scope of the claim. In such cases, the aforementioned specific problem may not be considered as the basis for the inventive step analysis unless the claim is limited in such a way that substantially all embodiments encompassed by it show the desired effect (see, for example, T 939/92, OJ EPO 1996, 309, Reasons, point 2.6, where the board was not satisfied that substantially all claimed chemical compounds were likely to be herbicidally active). Such limitation is typically achieved by narrowing one or more features (e.g. a temperature or concentration range within a chemical process) and/or by adding one or more limiting features. The above principle, as it was elaborated in the often-cited decision T 939/92, just specifies the further general principle that the entire or substantially the entire claimed subject-matter must fulfil the patentability requirements.

Likewise, a computer-implemented invention may have technical character and a feature may contribute to the technical character of the invention with respect to only parts of the claimed subject-matter.

Example: An increased speed for an inventive data transmission method (constituting the technical effect) can only be achieved if the size of transmitted data packets exceeds a certain minimum size, see figure below. In such a case, it may be necessary to limit the size of the data packets accordingly in the corresponding claim feature. Otherwise, there will be possible embodiments falling under the claimed subject matter which achive the effect of increased speed (embodiments having the data packets exceeding the certain minimum size) and possible embodiments falling under the claimed subject matter which do not achieve the effect of an increased speed (embodiments in which the data packets do not exceed the specified minimum size).

The limitation of the claimed subject-matter to a scope for which a technical effect may be acknowledged can be achieved by adding further limiting features, such as steps establishing an interaction with external physical reality.

Claimed invention has to be technical over the whole scope of the claim

Following the COMVIK approach, a feature is only considered for inventive step if and to the extent that it contributes to the technical character of the claimed subject-matter. A pre-requisite for meeting the requirement that the claimed invention is inventive over the whole scope of the claim is that it is also technical over the whole scope. Consequently, the requirement is not met if the claimed feature in question contributes to the technical character only for certain specific embodiments of the claimed invention, see example above.