This decision concerns the classification of emails where a user flags spam in addition to a computer-implemented method. This is considered to be a de-automation of a computer-implemented method. De-automation is not, according to the Board, a technical solution to a technical problem.

Object of the Invention:

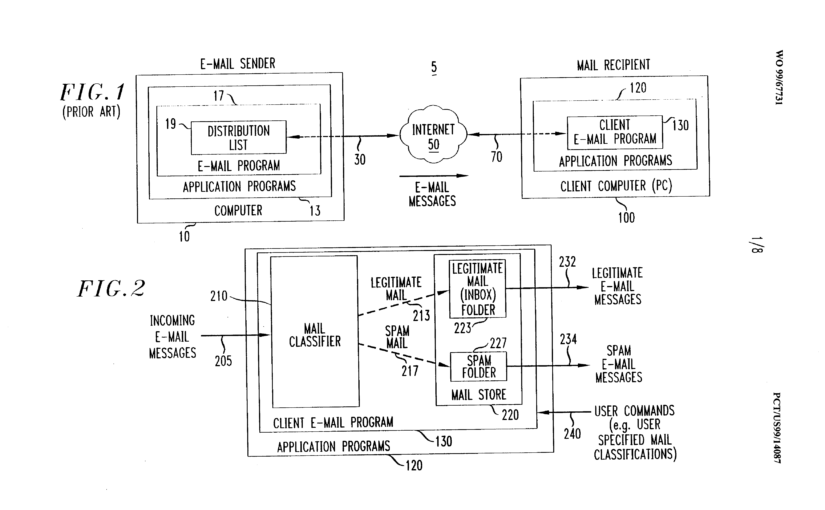

- the invention concerns the classification of emails, e.g. as either spam or legitimate mail

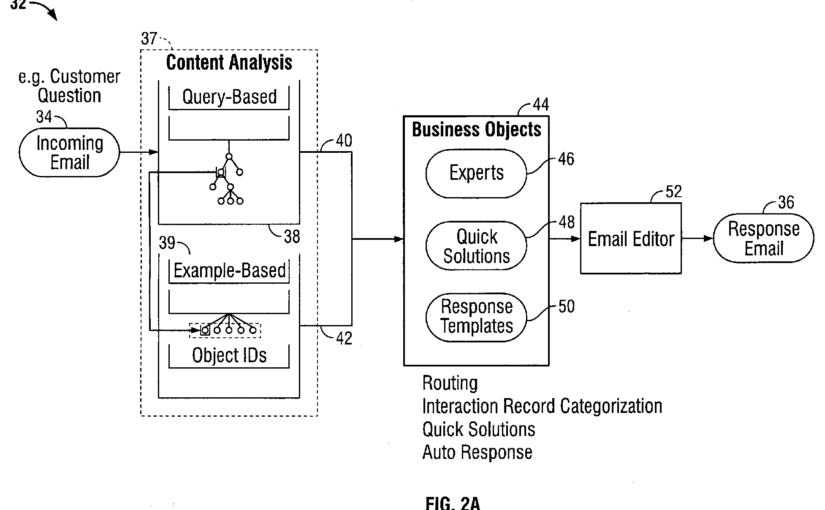

- an incoming email is first analysed to determine whether it contains one or more features in a set of predetermined features that are particularly characteristic of spam

- two types of feature are used: word-oriented and “handcrafted“

- the former refers to the presence of particular words, or stems of words, the latter to features determined through human judgement alone

- examples of a handcrafted feature is a sender address, since most spam messages are sent at night from “.com” or “.net” domains

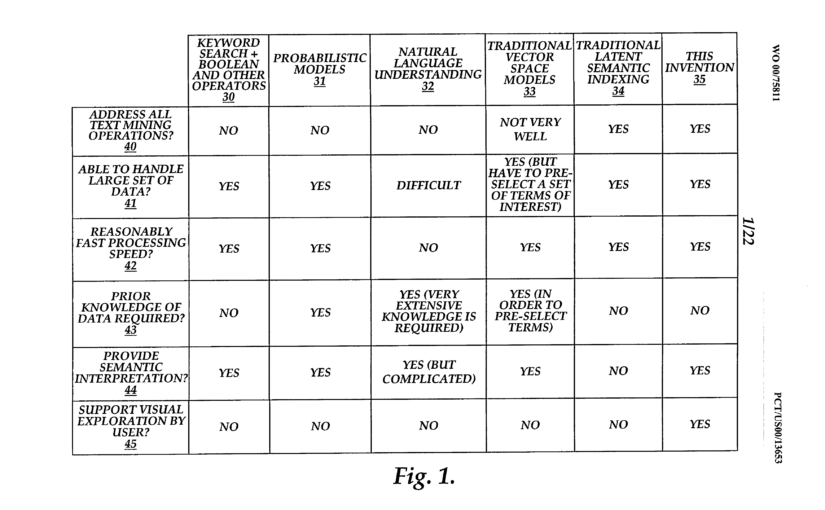

Board I (inventive step):

- the Board agrees with the Examining Division that the classification of messages as a function of their content is not technical per se

- it is immaterial whether the messages are electronic messages, because, even though an email has technical properties, it is the content of the email that is classified

- mathematical methods as such are not technical and the application of a mathematical method as such in a non-technical analysis of message content does not change that

- if there is a technical effect, it can only reside in the automation of the email classification using a computer

- the technicality of the computer is not enough to establish a technical effect of any method that it executes

Appellant I (inventive step):

- a classification based on a combination of “handcrafted features” and “word oriented features” had the technical effect of reducing processing load

Board II (inventive step):

- the Board is not persuaded that the alleged effect is actually achieved by the invention

- there is no link between the word-oriented and handcrafted features, so that the latter reduces the processing involved in the former

- the handcrafted features are, rather, a different class of features that the user considers indicative of spam, but which cannot be expressed in terms of the presence of individual words

- simply adding a second class of features to the analysis increases the load rather than reducing it

- furthermore, the Board does not consider that the de-automation of a computer-implemented method, by making a human perform steps that a computer could do automatically, is a technical solution to a technical problem

- any reduction in computer processing would be a mere consequence of the de-automation

- handcrafted features relate to information content that is considered as indicative of spam

- including such features in the analysis might, if well chosen, improve the quality of the classification, but the designation of a second class of features does not provide a technical effect

Appellant II (inventive step):

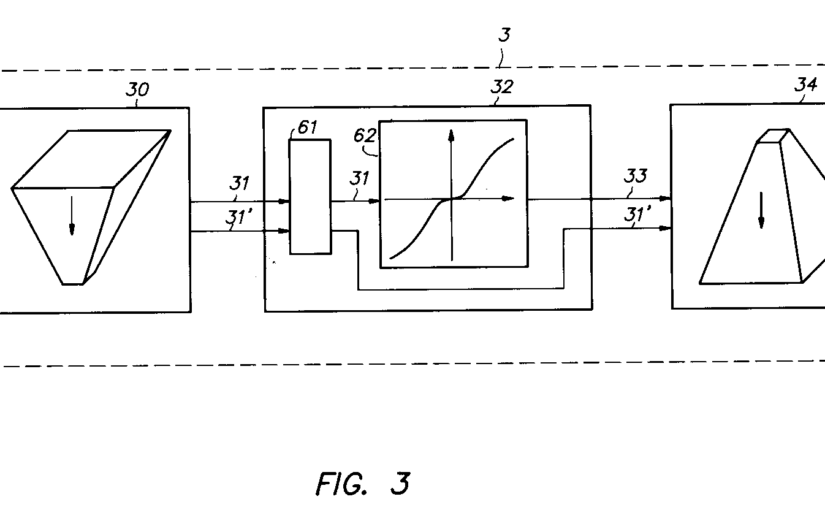

- the appellant argued, however, that there was a technical effect in the particular combination of an SVM and a sigmoid function

- performing the method in two stages, first using an SVM, and then applying an adjustable sigmoid function as a threshold to the output of the SVM, reduced the processing load, which reduced the complexity of the computer implementation

- thus, the invention was motivated by technical considerations of the computer implementation

Board III (inventive step):

- the Board is not persuaded by the appellant’s arguments on this point

- the Board does not find support, anywhere in the application, for the classifier being updated by adjusting the sigmoid parameters alone, without retraining the SVM

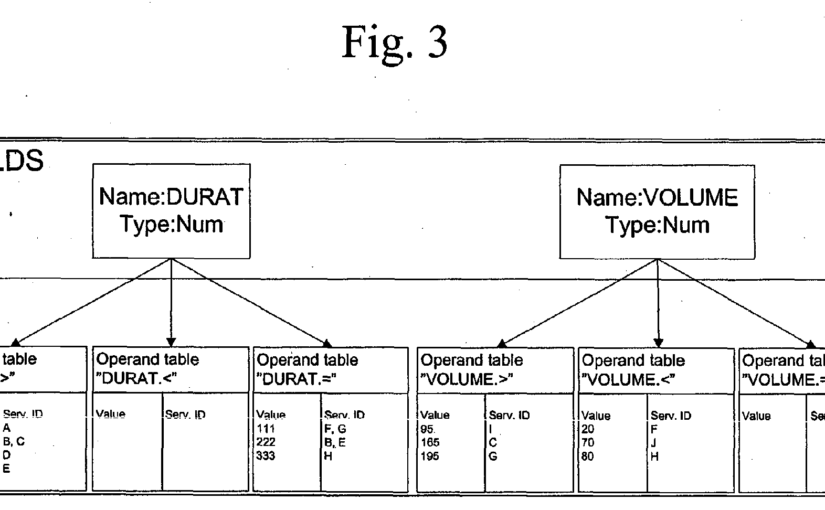

- the generation of parameters for the classifier during the training phase involves two steps:

- first the weight vector w is determined by conventional SVM training methods

- second the optimal sigmoid parameters are calculated by using a maximum likelihood on the training data

- there is nothing to suggest that re-training may involve only one of those steps, or that the classifier may be updated by simply adjusting the parameters A and B

- on the contrary, it is the teaching of the application that, when the conditions of what is considered as spam change (e.g. when the user reclassifies a message) the whole classifier is retrained

- furthermore, the Board does not consider that reducing the complexity of an algorithm is necessarily a technical effect, or evidence of underlying technical considerations

- that is because complexity is an inherent property of the algorithm as such

- if the design of the algorithm were motivated by a problem related to the internal workings of the computer, e.g. if it were adapted to a particular computer architecture, it could, arguably, be considered as technical (T 1358/09 referring to T 258/03)

- however, the Board does not see any such motivations in the present case

- thus, the Board is not persuaded that the use of an SVM in combination with a sigmoid threshold function contributes, technically, to the the computer implementation

- the Board rather considers this to be a mathematical method

- the technical implementation of the method consists in programming the computer to perform the method steps

- this would have been a routine task for the skilled programmer

- –> no inventive step