In this decision the appellant argued inter alia, that it is not possible to prove the expected technical effect and that this obliged the board to accept the effect unless it could “falsify” it.

Object of the Invention:

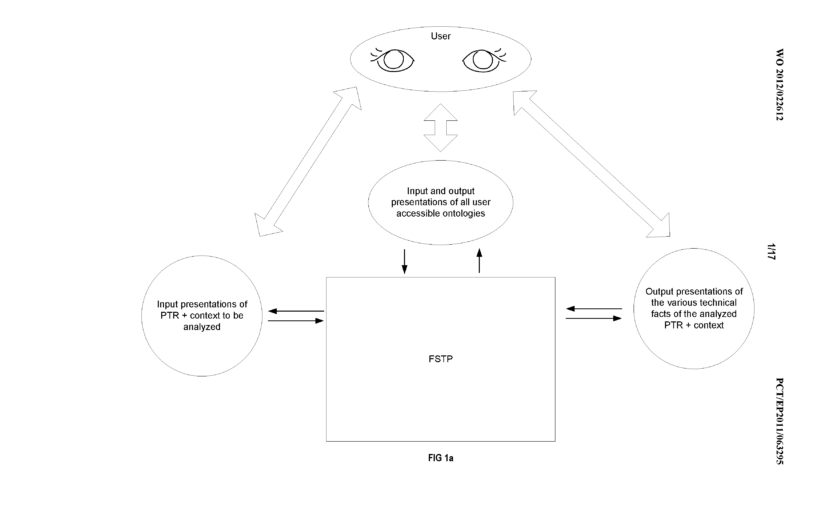

- the application relates to what is called the “configuration of a system-of-systems“

- the term “system-of-systems” is said to have arisen in the systems engineering community, where it “reflects the concepts and developments” of real systems such as “smart grids, integrated supply chains, collaborative enterprises, and next-generation air traffic management“

- a system-of-systems is “a collection of independent systems that work together to create a new, more complex system which offers more functionality and performance than simply the sum of the constituent systems“

- configuration of a system-of-systems is said to be “the task of selecting the optimal subset of component systems, that can perform the required task“

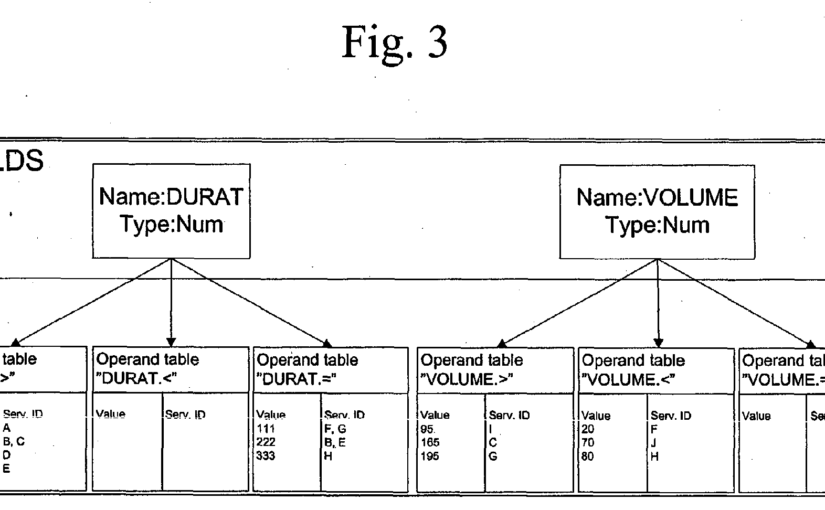

- the problem/task is rephrased in mathematical terms as a selection problem

- the relevant “characteristics” C of any system-of-systems SoS are defined as a set of pairs of attributes A and values from a set Domain(A) of all values which the respective attributes can take: Hence, the set of all possible such characteristics is C(SoS) = union of all attribute-value pairs Ai x Domain(Ai)

- the available components for any particular system are given as a set S of components Si, each having some characteristics: Thus C(Si) is a subset of C(SoS) for any Si

- the required characteristics are given as a subset of all possible ones too: C(R) is a subset of C(SoS)

- the configuration problem is then said to be the problem of finding an “optimal” subset Simpuls of the available components S so that their characteristics include the required ones: C(R) must be a subset of C(Simpuls)

- the notion of optimality is not defined in the application

- the declared objective of the invention is to solve this “system-of-systems configuration problem” with “membrane computing“, which is disclosed as being “a variation of” P-systems, a computational model “inspired” by biological processes

- the invention is said to rely on “a new kind of solver” which is “constructed using membranes, also called P-systems, and uses metaphors of chemical reactions occurring in living cells”

Appellant I (issue to be decided)

- use of “membrane computing” is the only difference over D1

- this difference has the effect of making it “possible to solve the occurring NP-hard problems […] in linear time”

- the objective technical problem solved by the invention thus has to be seen as “improv[ing] the time behavior of a method for the configuration of a system-of-systems“

- the claimed invention involves an inventive step because “there is no teaching in the prior art that would have prompted the skilled person, faced with the objective technical problem, to modify” D1 “by means of membrane computing“

- a “skilled person, confronted with the invention and with the information about” D2 “would accept” that by using “membrane computing” the “occurring NP-hard problems in the method” for the configuration of a complex system-of systems “can be solved in linear time“

- D2 “is conclusive proof” of “the claimed technical effect“

- “it is principally not possible for the applicant to prove the expected technical effect“, suggesting that the invention was “a theory in the empirical sciences“, which, according to Sir Karl Popper, “can only be falsified“

- this obliged the board to accept the effect unless it could “falsify” it

Board I (clarity)

- Claim 1 refers to “configuration of a system-of-systems without defining either “system-of-systems” or the problem of “configur[ing]” one, apart from mentioning that a “components system” has “roles described by […] participation statements” and “a set of requirements” which a configuration has to “fulfill”

- both terms are unclear

- there is no indication in the application that the term “system-of-systems“, or the problem of configuring one, has an established clear meaning in the art

- the application itself uses these terms in two significantly different ways […]

- D1 stresses further differing aspects of a “system-of-systems“, namely that the system components are related to each other by “use” relationships

- Claim 1 states that the configuration of the system-of-systems is computed “by means of membrane computing“

- the term “membrane computing“, and the notion of computing something “by means of” membrane computing, to be unclear in this generality […]

- in response to the board’s objections relating to clarity, the appellant has merely asserted that the claims are “clear enough” for the relevant skilled person

- this sweeping asserting does not sway the board’s opinion

- in this respect it is only of passing relevance that the skilled person is insufficiently characterised as having an unspecified “academic” education and “scientific work experience”

- claim 1 does not specify in clear terms the problem addressed (“configuration of a system-of-systems”) or the solution proposed (at least with regard to the phrase “by means of membrane computing”) and is thus unclear

Board II (further remarks)

- since claim 1 does not specify the problem to be solved or its solution, it is impossible to determine the complexity class of the problem or the computational complexity of the solution

- for this reason alone, the appellant’s allegation that the claimed invention solved “the occurring NP-hard problems […] in linear time” is without merit

- the board notes at this point that computational complexity theory is not, as the appellant seems to suggest, an empirical theory which is not amenable to proof

- to the contrary, complexity theorems are established by mathematical proof and their limits are precisely indicated

- therefore, if the appellant’s inventive step argument turns on an improved time behaviour, a rather specific one in particular, it is for the appellant to establish that the proposed solution has the claimed time complexity, and in which situations or under which circumstances it applies