In this decision the Board gives far-reaching statements for an “implied technical use” and “what is technical” based on G 1/19.

Object of the Invention

- the application relates to automated assessment of scripts written in examination, in particular English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) examinations

- the object is to provide a computer system that can automatically grade text scripts [and provide grades] that correlate well with the grades provided by human markers

Examining Division:

- distinguishing features merely representing mathematical or linguistic operations and entities, implemented on a general-purpose computer

- distinguishing features are not directed to a specific technical implementation going beyond the common use of a general-purpose computer

- distinguishing features are not limited to a technical purpose, since it is not specified how the input and the output of the sequence of mathematical or linguistic steps relate to a technical purpose, so that said it would be causally linked to a technical effect

- grading text scripts is not considered as serving a technical purpose

Appellant:

- the problem addressed is “providing a computer system that can automatically grade text scripts [and provide grades] that correlate well with the grades provided by human markers“

- distinguishing features reflected “further technical considerations“, for which case it stated that G 3/08 “guaranteed” that a technical character is present

- invention provides a technical contribution in the field of “educational technology”, defined as “the combined use of computer hardware, software, and educational theory and practice to facilitate learning”

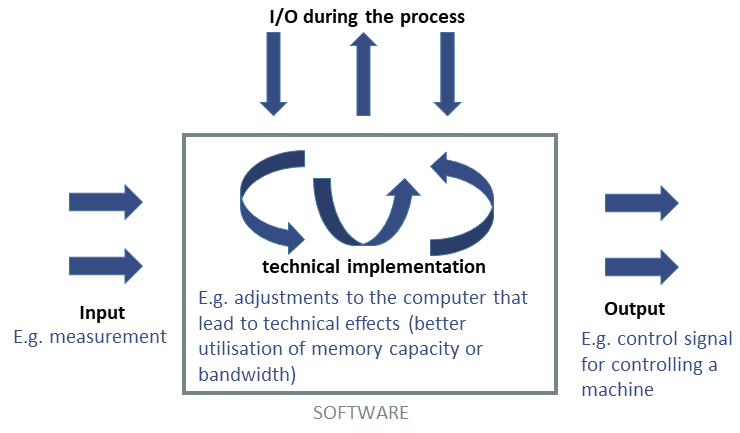

Board (part I) (technical effect within the computer):

- the model is not based on technical considerations relating to the internal functioning of a computer (e.g. targeting specific hardware or satisfying certain computational requirements)

- the preference ranking is chosen merely according to its educational purpose, which does not relate to any effects within the computer

- the claimed training procedure might constitute a technical contribution to the state of the art (see e.g. G1/19, reasons 33); taken alone, however, this is a mathematical method, so this contribution is in the – excluded – field of mathematical methods (see T 0702/20 and T 0755/18, catchwords) and is therefore not a patentable contribution

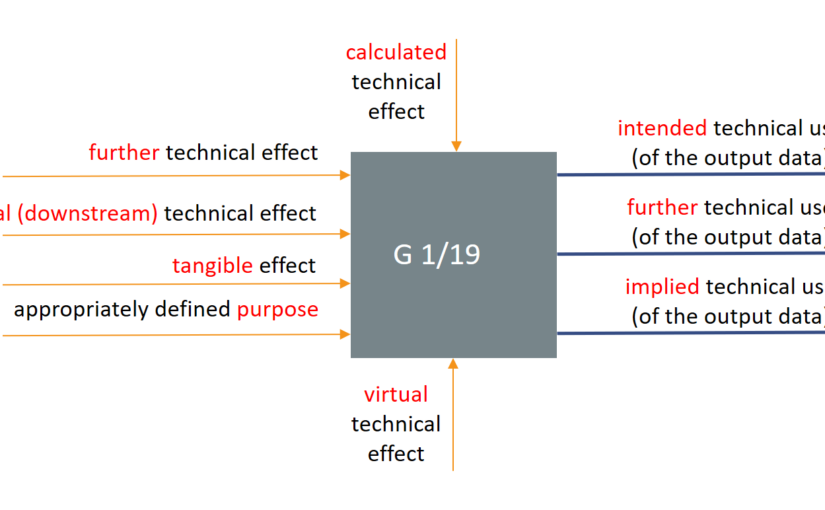

Board (part II) (technical effect via “implied technical use”):

- what remains as a potentially patentable contribution is the purpose of the claimed system to provide an automated tool for script grading (since no technical effect within the computer is established)

- questions to be answered are (i) whether the problem is, or implies, a technical one, and (ii) whether it is actually solved (T 641/00, reasons 5 and 6)

- question (ii): the human grading process is a cognitive task in which the marker evaluates the content of the script to assign a grade

- the assigned grade depends on the content of the scrip itself, but is also at least partly subjective: the marker will have preferences as to style and language, and will be influenced by experience and grades assigned to scripts in the past

- it is doubtful that the problem of automating script grading is defined well enough that one can properly assess whether it has been solved, i.e. in the sense that it provides a system that can actually replace different human markers and provide “correct” grades

- the invention may be useful, as the for the (self-)evaluation of linguistic competences by students

- it is assumed that the problem, as qualified by the Appellant, is solved

- under this assumption, there is a first argument that any automation of human tasks, irrespective of the task, is sufficient to conclude that a technical problem is solved, as it reduces human labor

- this argument contradicts the requirement of G 1/19 that there must be a technical purpose

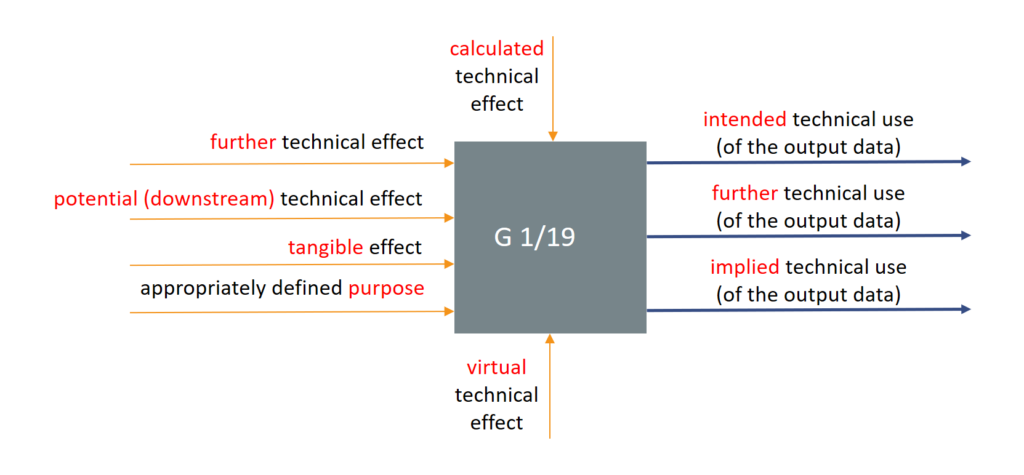

- G 1/19 was related to computer-implemented simulations, its reasons apply to computer-implemented methods other than simulations as well

- Enlarged Board stated that “information which may reflect properties possibly occurring in the real world […] may be used in many different ways“, that “a claim concerning the calculation of technical information with no limitation to specific technical uses would therefore routinely raise concerns with respect to the principle that the claimed subject-matter has to be a technical invention” (reasons 98) and that “[if] the claimed process results in a set of numerical values, it depends on the further use of such data (which use can happen as a result of human intervention or automatically within a wider technical process) whether a resulting technical effect can be considered in that assessment” (reasons 124), and concluded that “such further [technical] use has to be at least implicitly specified in the claim” (reasons 137)

- therefore, the argument that a technical problem is already solved by the mere provision of any automated tool cannot succeed

- it is assumed that the claimed invention serves the purpose of supporting its users in evaluating linguistic competences

- the question remains whether the assessment of linguistic competences, or maybe merely providing a grade, is a technical purpose

Board (part III) (What is technical?):

- Appellant considers that automated grading makes a technical contribution in the field of “educational technology” and, if the Board disagrees, asks the question “what is a technical field?” or “a field of technology?”

- the express reference to “fields of technology” in Article 52(1) EPC, introduced with the EPC 2000 in order to bring Article 52 EPC in line with Article 27(1) TRIPS, was not intended to change the established understanding that patent protection is “reserved for creations in a technical field“, i.e. involving a “technical teaching […] as to how to solve a particular technical problem” (see OJ EPO Special edition 4/2007, 48, but also G 1/19, reasons 24, and T 1784/06, reasons 2.4)

- the field of “educational technology” as defined by the Appellant is a rather inhomogeneous one, covering insights from – and presumably contributions to – a wide range of “fields“, technical ones and non-technical ones

- it appears questionable that this field can be considered a technical one as a whole (however, this question is not decisive)

- what is decisive, according to established case law of the Boards of appeal, is whether the invention -makes a contribution which may be qualified as technical in that it provides a solution to a technical problem

- if this is the case, a contribution to a field of technology may be said to also be present

- it is noted that the “field” of this contribution may be different from the one to which the patent more generally relates: for instance, inventions within the broad field of “educational technology” may make contributions in the field of computer science

- in G 1/19, the Enlarged Board followed its earlier case law and “refrain[ed] from putting forward a definition for ‘technical’“, because this term must remain open (section E.I.a, especially reasons 75 and 76; see also OJ EPO Special Edition 4/2007, 48)

- the Enlarged Board provided considerations as to what may be considered technical

- the Enlarged Board had suggested that a technical effect might require a “direct link with physical reality, such as a change in or a measurement of a physical entity” (see T 489/14, reasons 11)

- the Enlarged Board accepted that such a “direct link with physical reality […] is in most cases sufficient to establish technicality” (reasons 88) and, in this context, that “[it] is generally acknowledged that measurements have technical character since they are based on an interaction with physical reality at the outset of the measurement method” (reasons 99)

- the Enlarged Board also stressed that an effect could also be “within the computer system or network” (i.e. internal rather than “(external) physical reality”, see G 1/19, reasons 51 and 88)

- the Enlarged Board recalled that potential technical effects might also be sufficient (see also reasons E.I.e), i.e. “effects which, for example when a computer program […] is put to its intended use, necessarily become real technical effects” (reasons 97)

- the Enlarged Board considered that calculated data, while “routinely raising concerns with respect to the principle that the claimed subject-matter has to be a technical invention over substantially the whole scope of the claims” might contribute to a technical effect by way of an implied technical use (reasons 98 and 137), “g. a use having an impact on physical reality” (reasons 137)

- while the Enlarged Board has thus found that a direct link with physical reality may not be required for a technical effect to exist, it has, in this Board’s view, confirmed that an at least indirect link to physical reality, internal or external to the computer, is indeed required

- the link can be mediated by the intended use or purpose of the invention (“when executed” or when put to its “implied technical use”)

- returning to the case at hand, the Board finds that automated script grading, by itself or via its intended use for evaluating linguistic competences, does not have an implied use or purpose which would be technical via any direct or indirect link with physical reality

- the claimed computer-implemented method of automated script grading does not provide a contribution to any technical and non-excluded field, be it by way of how the automation is carried out, or by way of its use

- à no inventive step

Board (part IV) (Referral to the Enlarged Board of Appeal):

- the case law of the Boards of Appeal on the question of what is “technical” or a “field of technology” is sufficiently uniform (see in particular G 1/19) so that a referral to the Enlarged of Appeal is not required

- the term “educational technology” is too vague to be relevant for deciding the present case

- even within a field of technology a patentable invention must be shown to solve a technical problem

- in the present case, the Board was unable to identify a specific technical problem solved by the invention

Summary

- Appellant: problem is to provide an automated tool for script grading that correlate well with the grades provided by human markers

- Board: no technical effect within the computer

- Board: doubtful that problem is solved

- Board: it is assumed that the problem is solved

- Board: based on G1/19 the argument that a technical problem is already solved by the mere provision of any automated tool cannot succeed

- Board: it is assumed that the claimed invention serves the purpose of supporting its users in evaluating linguistic competences

- Board: the question remains whether the assessment of linguistic competences, or maybe merely providing a grade, is a technical purpose

- Appellant: considers that automated grading makes a technical contribution in the field of “educational technology” and, if the Board disagrees, asks the question “what is a technical field?” or “a field of technology?”

- Board: the field of “educational technology” as defined by the Appellant is a rather inhomogeneous one, covering insights from – and presumably contributions to – a wide range of “fields”, technical ones and non-technical ones

- Board: it appears questionable that this field can be considered a technical one as a whole (however, this question is not decisive)

- Board: it is decisive whether the invention makes a technical contribution

- Board: at least an indirect link to physical reality is required

- Board: link can be mediated by the intended use or purpose of the invention

- Board: automated script grading, by itself or via its intended use for evaluating linguistic competences, does not have an implied use or purpose which would be technical via any direct or indirect link with physical reality

- Board: not inventive