This section discusses arguments raised in the course of referrals proceedings in G1/19 regarding to support the technical nature of the simulated system. This chapter is based on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 122 to 126.

Skilled person of the simulation

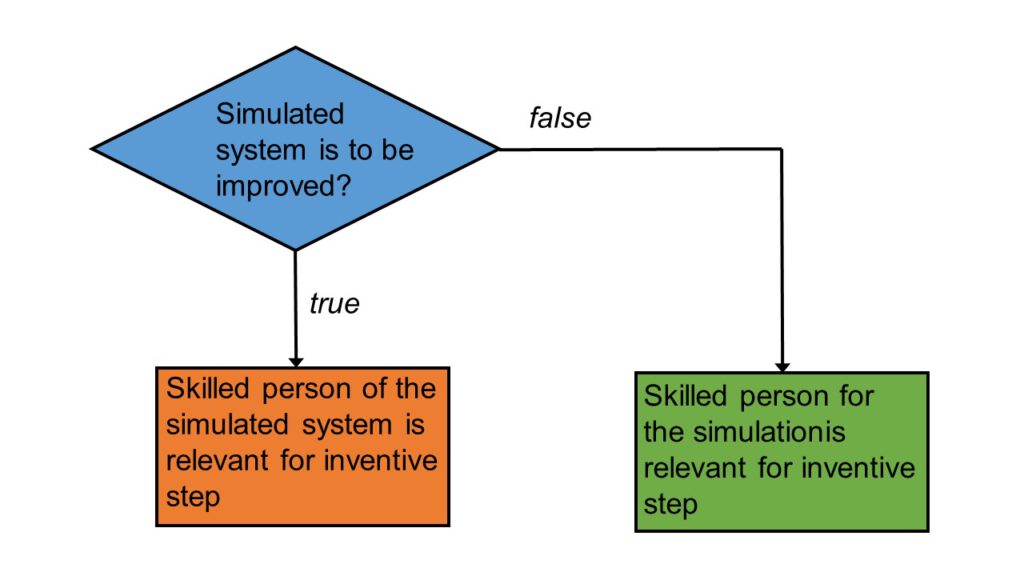

It was argued in the course of referrals proceedings in G1/19 that a simulation is of a technical nature and has technical effects if the relevant skilled person is a technically skilled person in the field of the simulated system or process (see e.g. the comments of the President of the EPO, points 23 to 25). This argument is partly based on T 817/16 (see Reasons, point 3.12), which relies on the (technically) skilled person in order to distinguish between technical and non-technical features. This approach may be suitable in some cases but may prove difficult in others where the skilled person for the simulation is different from that for the system represented by the model underlying the simulation. The skilled person is relevant for inventive activity. A technical or non-technical system represented in a simulation process is usually part of the prior art and determines the basis of the simulation.

Unless this system is to be improved (not just simulated), the skilled person of this field is less relevant than the skilled person for the simulation (and/or its function), which is the subject-matter of the invention, please see figure below.

Is avoiding the need to build certain prototypes a technical effect?

At least one amicus curiae brief in G1/19 argued that avoiding the need to build certain prototypes is a technical effect. This argument is not convincing because the decision to build or not to build a prototype is a business decision made by humans. In a similar way, it could be argued that forecasting bad weather results in lower fuel consumption. This technical effect is not the direct consequence of the output of the weather forecasting process but only occurs if, for example, human decisions are taken to refrain from planned leisure trips by car on a rainy day.

Equating the result of the simulation to the “technical effect”

Another argument, which underpins some of the existing case law on numerical simulations and was also put forward in the comments of the President of the EPO, is based on equating the result of the simulation to the “technical effect” to be considered in the problem-solution approach (point 29). The argument that the technical effect thus goes beyond the simulation’s computer implementation and its numerical result is used, inter alia, when the simulation is described as an (intermediate) step in the production of a technical system. The “Logikverifikation” decision of the German Federal Court of Justice (Case X ZB 11/98, GRUR 2000, 498, see referring decision, Reasons, point 21) accepted this argument.

In the Enlarged Board's view, however, only those technical effects that are at least implied in the claims should be considered in the assessment of inventive step.

If the claimed process results in a set of numerical values, it depends on the further use of such data (which use can happen as a result of human intervention or automatically within a wider technical process) whether a resulting technical effect can be considered in that assessment. If such further use is not, at least implicitly, specified in the claim, it will be disregarded for this purpose.

Technical considerations relating to a potential contribution to the technical character of the simulation can be relevant for the inventive step assessment

Several amicus curiae briefs in G1/19 relied on decision T 769/92 (OJ EPO 1995, 525) to support the argument that technical principles underlying the simulated system or process are sufficient to establish a technical problem. Headnote I of said decision sets “technical considerations concerning particulars of the solution of the problem the invention solves” as a requirement. As mentioned in the referring decision, this criterion was used in T 769/92 to apply the eligibility hurdle of Articles 52(2)(c) and (3) EPC, since that decision still followed the “contribution approach” (Reasons, point 34 of the referring decision, quoting G 3/08, Reasons, points 10.6 and 10.7). While it is correct that similar “technicality” considerations apply with respect to the two hurdles of the COMVIK approach (see G 3/08, Reasons, point 10.13.1), it is the second hurdle which is relevant for Article 56 EPC. It requires that any technical considerations must pertain to the invention, i.e. to the simulation, rather than the prior art including the simulated system or process.

The technical considerations which may be required in order to understand the simulated system or process are not necessarily relevant to whether the invention solves a technical problem by producing a technical effect.

According to the COMVIK approach, “technical considerations” should result in contributions to the technical character of the invention itself. Applied to computer-implemented simulations, only technical considerations relating to a potential contribution to the technical character of the simulation can be relevant for the inventive step assessment.

Closer look at T 769/92

It appears that decision T 769/92 – even though issued many years before COMVIK – applied similar principles. The underlying claims concerned a computer-implemented invention for use in a commercial context (“at least financial and inventory management”, see claims 1 and 2 quoted in point V of the Facts and Submissions). The deciding board considered that it was not relevant whether the “management” features related to managing business processes or technical processes, but it mentioned that the exclusion from patentability would not apply to inventions “where technical considerations are to be made considering the particulars of the implementation” (Reasons, points 3.2 and 3.3). The claimed invention was characterised, in particular, by the independent management of two different types of data using a single common user interface in the form of a “transfer slip” (Reasons, points 3.7 and 3.8).

In other words, the “technical considerations” addressed in the Headnote of the decision refer to technical considerations necessary in the context of the implementation of the data processing, not to the nature of the data processed or to the business or technical context in which the invention is applied.